Green Source DFW columnist Amy Martin recounts her journey through six decades in the green counterculture. Photo by Dianne Frossard.

April 21, 2020

Every day was Earth Day as a kid growing up in a maladjusted family. Outside was a refuge from the dysfunction and the place to be. Even when too young to venture much beyond the yard, I found a universe of wonder. Every hidden shady spot tucked behind a shrub, each tiny tunnel dug by an animal, offered infinite possibilities and endless hours of amazement.

Nature shaped my toddler self. Its metaphors of interconnectedness seeped into me before I had words to describe them. The world above, in the boughs of trees, the Moon and sky beyond, and its mirror below, the mysterious dark realm of dirt. There I was suspended in the middle. The Church of the Backyard captivated me. Even with the food-chain carnage of bugs consumed by birds that are eaten by cats, at least it made sense.

Photo by Julie Thibodeaux.

Photo by Julie Thibodeaux.

My world expanded as I grew older. The neighbor’s yard and its overgrown back section. The creek behind the house leading to adventure. The park down the road with genuine woods and wild things. Family car vacations provided new landscapes to ogle. The Golden Book Encyclopedia took me to places I was unable to go.

It was bliss — until a local Sierra Club representative visited my class in 1970 for Earth Day. My naive bubble got popped. For the first time I realized the nature I loved was under siege and wildlife slaughtered by the score. Even in my city, the air I breathed was polluted and the water tainted.

REBEL WITH A CAUSE

Unleashed was the activist within. The Sixties rebellion roared well into the 1970s. Progressive causes abounded — Watergate, Vietnam, Kent State, civil rights — and anger at the assassinations was profound. The Comanche Peak Nuclear Power Plant in development at Glen Rose west of Fort Worth, emerged as the dominant eco topic. Blessed at the time with two daily newspapers, I wrote letters to the editor almost weekly.

Photo by Julie Thibodeaux.

Photo by Julie Thibodeaux.

Suddenly, a plethora of ecological books demanded to read. So grateful for libraries! At the top: Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and anything by Edward Abbey. My copy of Diet for a Small Planet was stained and dog-eared from cooking. The annual Whole Earth Catalog was an evolving eco primer. The classics of John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and Henry David Thoreau connected me to a community going back centuries.

I also consumed spiritual texts of the day: Steppenwolf and Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse, The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran, Be Here Now by Ram Dass. They fused with my Earth advocacy. The Moon landing further fueled my belief in an evolving humanity. All to a soundtrack of late Beatles and early Yes.

Activist Amy was too much for the public-school powers to abide. The underground newspapers they suspected I was producing didn’t help my case. Technically, the expulsion was for wearing a shirt made from two decorated hand towels hand-sewn together and suspended from shoestring straps. I considered it textile recycling. Violated the dress code evidently.

HIPPIE HIGH SCHOOL

I ended up in a series of weird counter-culture high schools held wherever the space was free or cheap. The poolhouse of a mansion (that was fun!), for instance, or an abandoned kindergarten (we had to sit in miniature chairs!). Jasmine, my Labrador retriever, attended with me. At the last school, we all watched aghast as the principal was taken away in handcuffs. Jasmine had always barked at him. She knew.

I ended up in a series of weird counter-culture high schools held wherever the space was free or cheap. The poolhouse of a mansion (that was fun!), for instance, or an abandoned kindergarten (we had to sit in miniature chairs!). Jasmine, my Labrador retriever, attended with me. At the last school, we all watched aghast as the principal was taken away in handcuffs. Jasmine had always barked at him. She knew.

After that school debacle, I landed at Walden Preparatory, ensconced in a Frank Lloyd Wright house tucked away among trees. The student body was nearly 100 percent hippie and surprisingly cynical. Well read, but not active. Their idea of celebrating Earth Day was to roll up a fatty and head off to the woods.

My boyfriend and I gained horticulture credits by resurrecting an old greenhouse and garden on the Walden grounds. We screened off the students’ pot plants behind strategically placed clutter and taught ourselves how to become farmers. I did a Watergate 101 paper for extra credit and a few teachers had me present it in front of their space-cadet students in my first foray as a writer/speaker.

FARM LIFE SANITY

But in the early 1970s, the cultural and military wars were at a fever pitch. Friends were dropping dead from overdoses and ending up in jail. Home was not a safe place to be. My innate optimism was getting battered. Just too intense for this gentle nature girl.

The back-to-the-Earth movement beckoned. I fled to become a cucumber farmer for Best Maid pickles, dragging my bewildered boyfriend (and future husband) with me. A little clapboard house three miles down a dirt road, water from a well, power when the lines weren’t blown down.

The back-to-the-Earth movement beckoned. I fled to become a cucumber farmer for Best Maid pickles, dragging my bewildered boyfriend (and future husband) with me. A little clapboard house three miles down a dirt road, water from a well, power when the lines weren’t blown down.

Earth Day didn’t exist in Red River County, about two hours east of Dallas. Neither did the news except for Paul Harvey on the radio every weekday at noon. The rural sanctuary was healing. There were wild acres to amble and a creek to follow, just like the bliss of childhood, even if I was also looking for cow patties with purple mushrooms.

Within a couple of years, the illusion of the romantic life of a farmer was in ruins. Farming I learned was an avocation marked by long hours and loneliness, physical and monetary risk, grueling manual labor, and dirt in every damn crevice of your body, barn and house. I grew to hate the smell of cucumbers.

BIRTH OF A WRITER

Occasionally, we’d trek to Dallas for supplies. On one of those trips I discovered a mimeographed newsletter, Over the Garden Fence. And there it was, an ad seeking writers. The topic they wanted covered? A series on nuclear power, specifically Comanche Peak Nuclear Power Plant. I penned an explanatory series on how nuclear power worked, from uranium mining to power generation to waste disposal. Not only was Activist Amy re-awakened, but a journalist was born, though under an assumed name. Nuclear activists then endured FBI harassment, so my nom de plume was A.R. Lewis.

Occasionally, we’d trek to Dallas for supplies. On one of those trips I discovered a mimeographed newsletter, Over the Garden Fence. And there it was, an ad seeking writers. The topic they wanted covered? A series on nuclear power, specifically Comanche Peak Nuclear Power Plant. I penned an explanatory series on how nuclear power worked, from uranium mining to power generation to waste disposal. Not only was Activist Amy re-awakened, but a journalist was born, though under an assumed name. Nuclear activists then endured FBI harassment, so my nom de plume was A.R. Lewis.

Somehow my little endeavor garnered the attention of Ned Fritz, grandfather of the Dallas environmental movement. Influential on a state level as well, he helped save the Big Thicket in East Texas, among other deeds, and led a group known as Texas Committee On Natural Resources, now called the Texas Conservation Alliance.

My editor excitedly called to tell me TCONR nominated us for an award. Winners would be announced at the Inwood Theater during a 1976 screening of All the President’s Men, about the journalists who uncovered Watergate. If memory serves, the event was part of Earth Day events in Dallas. Winning the award was the biggest thrill ever and still is.

NO NUKES!

I returned to Dallas a year later. Even harder than losing my marriage was no longer having a connection to land. I threw myself into the city’s environmental movement. Excellent rabblerousers like Jim Schermbeck, Kim Batchelor, Mavis Belisle and Lon Burnam (who later became a state representative) were gearing up to fight the Comanche Peak Nuclear Power Plant.

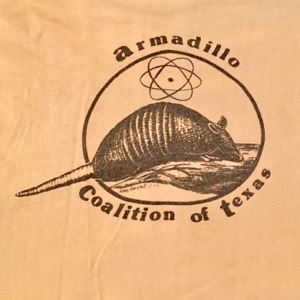

Armadillo Coalition of Texas t-shirt. Courtesy of Jim Schermbeck.

Armadillo Coalition of Texas t-shirt. Courtesy of Jim Schermbeck.

First, it was the Armadillo Coalition of Texas in 1977, still the best Texas activist group name ever, founded by Batchelor, Burnam and Schermbeck. Two years later, Comanche Peak Life Force formed solely to focus on civil disobedience, which was going on at other nuclear power plants around the nation. Parallel to them was Citizens Association for Sound Energy headed up by Juanita Ellis. I was proud to serve as a CASE clerical worker before wandering over to ACT, which was frankly more fun.

And what a force the Comanche Peak Life Force was. Although I never became a member, I was a fan. The group organized what was then, and probably still is, the state’s most significant act of civil disobedience by staging an occupation of Comanche Peak. On November 25, 1979, over 100 protestors (who were all trained in nonviolence) participated. Using a specially constructed ladder to scale a fence into the plant grounds, a ten-minute occupation by CPLF ensued. Activists chanted, sang and conducted media interviews.

CPLF protestors departed the plant as requested by authorities and boarded provided buses to the Somervell County courthouse. Police charged 48 with trespassing. Kick-butt defense attorneys, including Lewis Pitts and Tim Mills, were able to convince four out of six Glen Rose jurors to acquit.

Courtesy of Jon Whitsell.

Courtesy of Jon Whitsell.

Unwilling to let it go at that, CPLF organized more acts of civil disobedience at Comanche Peak. A second occupation in November 1979 attracted up to 300 participants and resulted in 100 arrests. The final occupation in July 1980, wound down with some 200 participants and 20 arrests.

Several CPLF members gathered in Glen Rose last June for the 40th anniversary of the first occupation, prompting Schermbeck to write on Facebook: “I'm proud to have been a part of this remarkable extended family, whose collective spirit was so contagious it was able to convince four out of six Glen Rose jurors we were ‘not guilty’ because we were trying to prevent the larger harm of an operating nuclear power plant.”

Comanche Peak Nuclear Power Plant ultimately came online on April 17, 1990, but never reached full planned capacity.

SEASONS OF EARTH DAYS

In any life as long as mine — six decades and counting — phases come and go. After the period of intense activism, I swung 180 degrees to a sybaritic period in my late 20s. While bartending my way through college, I ended up in music journalism, living the nightlife as well as writing about it.

All fun and games until a neurological affliction sobered me up. Like meeting Buddha on the road, a neurologist turned me around with life advice. “You want an answer for why you feel the way you do. I won’t do that until you get insurance. In the meantime, get as healthy as you can, which means quitting your job, and live for something outside yourself.”

Eco-activism turned out to be good for my health and career. I became a recycling activist and helped start the first neighborhood centers in Dallas. I called an editor at the Dallas Morning News to garner coverage of the effort and ended up writing a monthly page on recycling for them called Talking Trash. Earth Day was an official Big Deal at Talking Trash with a huge spread of articles that month.

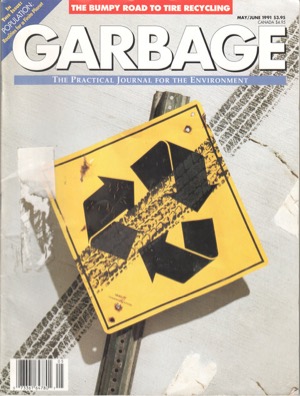

Garbage magazine, a gutsy and witty urban eco glossy, hired me away in the early 1990s. Earth Day was a Big Deal there, too. I created an Ask Garbage column on recycling and became the Dear Abby of trash, even invited onto national talk shows. Soon I expanded into writing features, including a groundbreaking series called Petrochemical Primer that explored the insinuation of synthetics into our daily lives and its cost.

Garbage magazine, a gutsy and witty urban eco glossy, hired me away in the early 1990s. Earth Day was a Big Deal there, too. I created an Ask Garbage column on recycling and became the Dear Abby of trash, even invited onto national talk shows. Soon I expanded into writing features, including a groundbreaking series called Petrochemical Primer that explored the insinuation of synthetics into our daily lives and its cost.

By the mid-’90s, I was back to my high-school roots, fusing a love of nature with spirituality. My band of volunteers and I staged seasonal celebrations and lunar events, culminating in the colossal Summer SolstiCelebrations at White Rock Lake. The outdoor festivals decimated my health. But I stayed with the indoor Winter SolstiCelebration for 20 years while operating a holistic news service called Moonlady News.

Amy Martin in her element. Photo by Katie Kelton.

Amy Martin in her element. Photo by Katie Kelton.

Now I’m fully in the eco pocket. I pen occasional features and the monthly North Texas Wild column for GreenSourceDFW. My free time is absorbed with nature outreach and activities with North Texas Master Naturalists. With public events on hold due to COVID-19, it feels a bit deflating not doing NTMN outreach for Earth Day. But the beautiful thing about Earth Day is that there will always be another one next year.

See more of our 50th Anniversary of Earth Day coverage.

Stay up to date on everything green in North Texas, including the latest news and events! Sign up for the weekly Green Source DFW Newsletter! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter. Also check out our new podcast The Texas Green Report, available on your favorite podcast app.