Nov. 4, 2019

Nov. 4, 2019

Texas native plants are being threatened by a convergance of risks - urban sprawl, invasive plants and climate change. Kim Taylor, a conservation research botanist at the Botanical Research Institute of Texas in Fort Worth, talks about the seed bank she and other botanists across the state are building to ensure the survival of Texas native plant species facing these pressures. The Texas Green Report podcast is a production of Green Source DFW and the Memnosyne Institute. Report by Marshall Hinsley. Above, seeds collected by BRIT. Photo by Haley Lilley.

Nov. 4, 2019

READ THE FULL TRANSCRIPT

Marshall Hinsley: How botanists are building a backup of the state’s native plant species in this episode of the Texas Green Report.

A production of Green Source DFW and the Memnosyne Institute. I’m Marshall Hinsley.

The third fastest growing state in the nation, Texas is losing wild habitat at a rapid pace. In swelling metropolitan areas such as the Dallas-Fort Worth region, every new shopping center being built, housing development under construction and road being paved means yet another portion of our natural landscape is buried under asphalt and concrete.

Outside of dense population centers, conversion of rural landscapes into farmland and fire suppression practices on ecosystems that depend on occasional natural wildfires to thrive add to the phenomenon of habit loss that’s pushed more than 450 native Texas plant species toward the rare, threatened or even endangered status.

Unless something is done about it, these species are doomed to vanish from the native Texas landscape.

That possibility doesn’t sit well with Kim Taylor, a conservation research botanist with the Fort Worth-based Botanical Research Institute of Texas, BRIT for short.

Kim Taylor: Plants really serve as the foundation for the entire ecosystem that we live in. All of the services all of the things that we use from the environment from the air we breathe to cleaning the water that we drink -- that's all done by plants. Without plants, we couldn't live in this world.

Kim Taylor: Plants really serve as the foundation for the entire ecosystem that we live in. All of the services all of the things that we use from the environment from the air we breathe to cleaning the water that we drink -- that's all done by plants. Without plants, we couldn't live in this world.

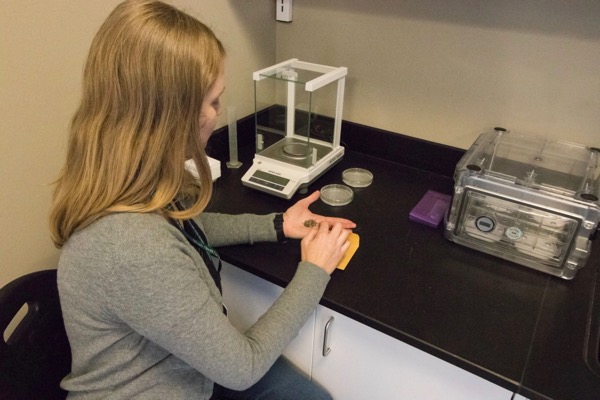

BRIT botanist Kim Taylor is overseeing a seed bank collection for Texas native plants. Photo courtesy of BRIT.

Marshall Hinsley: So, the institute has undertaken a monumental endeavor to create a huge seed bank of the native plant species in Texas, starting with the rarest and most threatened species and eventually including the entirety of the state’s unique flora.

After collecting seeds from wild populations at various sites, some of which are slated for development, BRIT botanists clean the seeds, seal them in moisture controlling containers and store them at minus 20 degrees celsius in an ordinary chest freezer. Those seeds can then remain viable for decades, even centuries says Taylor.

Kim Taylor: We're focusing on collecting seeds from wild populations. And those seeds essentially serve as a backup, or an insurance policy against extinction of that species.

So there's about almost 450 species of native plants that occur right here in Texas, anything from a wildflower to a cactus to a tree that are rare that are threatened for various reasons and have declining populations. And we're focused on getting those seeds into the seed bank. Most of the species, at least that we're focusing on right now occur nowhere else in the world but right here in Texas, so we're going out to these wild populations and collecting seeds directly from that source.

Marshall Hinsley: Among the species collected so far is the Comanche Peak Prairie Clover, which was discovered again in the 1980s after it was previously thought to be extinct. It occurs in just eight counties west of Fort Worth, and nowhere else in the world. Also in storage are seeds for Glandular, Blazing Star Gayfeather, collected from a city park in Dallas.

Kim Taylor: Hopefully our city parks will be protected. But we don't know what's going to happen to this land that's right here in an urban area so we wanted to make sure we could get that seed into the bank, just in case something happens to that population.

Marshall Hinsley: On the list of seeds to be collected next: Topeka Purple Coneflower, Osage Plain Falls Foxglove, and Hall’s Prairie Clover.

Kim Taylor: We're focused right now, in the beginning, on collecting species that are incredibly rare and expanding out, because those are the species that we’re most at risk of losing. And the purpose of the seed bank really is to be that backup. So we want to make sure we get those populations that the species that only have maybe one or two or 10 populations left in the wild, you know, a single catastrophic event like Hurricane Harvey, for instance, could come in and completely wipe out an entire species if it only has a couple of populations left. So we're trying to kind of hedge our bets, and make sure we can get those rare species first.

Marshall Hinsley: After which the botanists will then move on to more common species with the ultimate goal of securing a backup of every native plant in the state.

Among the rarest species Taylor says is on her personal list of priorities is an inconspicuous pink flower that blooms in late summer in East Texas.

Kim Taylor examines seeds in the lab. Photo by Haley Lilly.

Kim Taylor examines seeds in the lab. Photo by Haley Lilly.

Kim Taylor: It's called Texas screw stem. It's this tiny little, looks like a little green twig. It's not very attractive. But this species is so hard to find. We haven't, even though we've been working on this species for a couple years and our partners in Houston at Mercer Botanic Garden have been working on this species. We really haven't been able to get seed for this species. Individual plants only produce a couple of seeds each and when we find plants, we may only find one or two plants. So we don't want to take all of that feed.

Marshall Hinsley: BRIT coordinates with botanical organizations and botanists throughout the state, both to locate populations and to ensure that they don’t harvest too many seeds from the wild which could contribute to a species’ downfall.

Kim Taylor: We collect absolutely no more than 10 percent of the available seed. So the purpose of that is we want to get as much seed as we can because more seed we have, the more potential uses, things we can use that seed for in the future, but we don't want to harm the net the native population.

We work very closely with a number of collaborators. The Center for Plant Conservation is a nonprofit that we work closely with, but here locally in Texas, you know, some of our key partners of the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, as I'm sure many people are familiar with their work. We also work with Mercer Botanic Garden in Houston and the San Antonio Botanic Garden, as well as our own Fort Worth Botanic Garden.

Marshall Hinsley: Taylor says the seeds in cold storage aren’t just intended for release after some sort of doomsday scenario. They’re to be used for restoration efforts also, in state parks or on the land of landowners who share BRIT’s vision for restoring native habitat. The seeds could also be collected from a site where something like road construction will disturb a large area, and then be re-established along the roadside once construction is complete.

Although loss of habitat from land development is a more visible threat to Texas plant species, Taylor says emerging threats are eroding the ability of entire ecosystems to maintain thriving plant diversity throughout the state.

Kim Taylor: We're seeing a lot of populations being lost because of development. But also things like the spread of invasive species and invasive species, whether a plant or an animal can come in and change the ecosystem to a point where the species can't survive anymore. And the threat that we're concerned about more so in the future is really climate change, and how that's going to impact our species, especially species that only occur in very narrow areas. If our climate changes so much, are they going to be able to survive that new climate?

Marshall Hinsley: Taylor says the seed bank’s mission goes far beyond just keeping roadside stocked with beautiful wildflowers or state lands full of Texas’ rugged natural heritage. The seed bank is a response to the catastrophic harm we’ve caused to pristine ecosystems and the loss we’ve inadvertently caused to the diversity of plant life and the benefits plants bring to our lives.

Kim Taylor: Every species is unique, and every species has its own evolutionary history. And who am I to say that this species that has an evolutionary history as long as humanity doesn't deserve to be here?

From a purely ethical standpoint, I feel like we're the ones making these species rare. We're the ones driving them to extinction. It's our responsibility to protect them. But from a practical standpoint, we don't know enough about these species to know what their benefit to humanity could be. They may be the next medicine that can cure cancer; they may be a source of food that we haven't exploited yet. They may be a pivotal species to an ecosystem that once that species is gone, the entire ecosystem could collapse and lead to the extinction of several other species. So we just don't know enough to know what we can lose. So we can't really afford to lose anything.

Marshall Hinsley: For the Texas Green Report, I’m Marshall Hinsley.

You can learn more about BRIT and what Texans are doing to protect our state/s natural heritage at Green Source DFW.org.

Stay up to date on everything green in North Texas, including the latest news and events! Sign up for the weekly Green Source DFW Newsletter! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter. Also check out our new podcast The Texas Green Report, available on your favorite podcast app.