The former Lane Plating Works at 5322 Bonnie View Road in Dallas was declared a Superfund site in May. Photo courtesy of Googlemaps.

Jan. 15, 2019

Olinka Green’s broad, smiling face darkens to a frown, when the subject of the old Lane Plating plant in her southern Dallas neighborhood comes up.

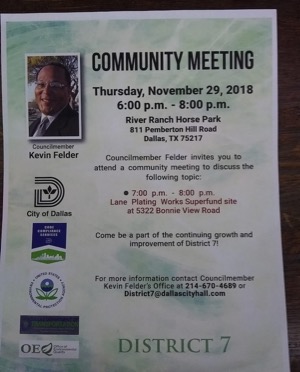

The 40-year resident of Highland Hills was researching environmental hazards, when she found serious ones way too close to home. Ills that look likely to linger, with federal cleanup years off. A community meeting in November left residents unsatisfied with scant information and propelled them to further action.

“I was calling EPA Region 6 in Dallas back last March, trying to inform myself,” Green said in a recent interview.

Highland Hills resident and activist Olinka Green shares information on the Lane Plating site at the Highland Hills Branch Library in November. Photo courtesy of Pamela Young.

Highland Hills resident and activist Olinka Green shares information on the Lane Plating site at the Highland Hills Branch Library in November. Photo courtesy of Pamela Young.

A long-time social activist, she’d been asked to give a community workshop on environmental action. She reached out to two staffers at the local Environmental Protection Agency office.

“Look up Superfund sites,” they suggested, steering her toward the agency’s list of the most toxic industrial and waste sites in the nation, ones that EPA has determined will require years of cleanup and monitoring to be safe for human proximity, and then designated for cleanup.

On the list, Green discovered a site only blocks from her home. The agency had been investigating it for Superfund designation since 2015, according to their public timeline.

Lane Plating Works had operated in Highland Hills since the 1950s, applying metal coatings to car bumpers and the like, just off Loop 12 and Interstate 45 on Bonnie View Road. It was shuttered in late 2015, when the owners declared bankruptcy.

“Shuttered” also describes much public information on Lane Plating’s environmental record and responses by state and federal agencies, it turns out.

Green and friend Alexandra Telecky visited the site, and found it chained off.

“We got involved,” Green said.

They started researching.

Lane, like other electroplating companies, used toxic metals including arsenic, cadmium, cyanide, chromium, lead and mercury — substances that cause cancer and damage the brain, kidneys and liver, as well as digestive, reproductive and nervous systems.

A wetland lies close by the old plant, between it and the newly named Barack Obama Leadership School for Boys. Two creeks drain the site, flowing to the Lemmon Lake fish hatchery and the Trinity River.

Hoping to pin down the health effects of the plant’s leaked chemicals, Green sought the help of Legal Aid of NorthWest Texas to file public information requests for EPA records.

Aaron Renaud, a paralegal with LANWT, uncovered a history dating back before 1985: company hazardous waste reports; Dallas Water Utilities inspection of the site; inspections by the state environmental agency Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, EPA and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Between late 2015 and late 2016, both TCEQ and EPA had documented violations and taken short-term measures to secure and remove toxic waste - as an April 7, 2017 memo from the director of the city’s Office of Environmental Quality informed the mayor and city council. An EPA 2016 report states almost 200,000 pounds of chemical waste had been removed.

The community apparently got no word of the situation all those years, according to Green and Renaud, not until shortly after OEQ’s April 2017 memo. Then-councilmember Erik Wilson had urged EPA administrators to hold a public meeting that February or March, before possible Superfund classification. On April 17, 2017, the Office of Environmental Quality did coordinate a community meeting on Lane Plating’s legacy at a neighborhood church.

“I saw very limited EPA notification of residents,” said Renaud.

Almost a year later, this past February, there was another meeting to give an update of the investigation. Notices of it apparently reached very few residents.

On May 15, 2018, EPA placed Lane Plating Works on the National Priorities List as a Superfund site - a first step to permanent cleanup.

Fast-forward six months. In November, EPA had scheduled a community meeting with responsible agencies. Announcements went only to the local library “and to the people who lived across the street from the plant,” said Green. Nevertheless, some 100 residents appeared at Highland Hills Branch Library. Publicity by Green, 300 new followers of her Facebook announcements, newly-minted activist Temeckia Derrough of nearby Joppa, and four grassroots groups had drawn a crowd.

Fast-forward six months. In November, EPA had scheduled a community meeting with responsible agencies. Announcements went only to the local library “and to the people who lived across the street from the plant,” said Green. Nevertheless, some 100 residents appeared at Highland Hills Branch Library. Publicity by Green, 300 new followers of her Facebook announcements, newly-minted activist Temeckia Derrough of nearby Joppa, and four grassroots groups had drawn a crowd.

The councilmember for Highland Hills’ District 8, Tennell Atkins, gave a short introduction and left. Representatives of EPA, TCEQ, Texas Health and Human Services, Dallas Water Utilities, OEQ and the NAACP attended.

“EPA wasn’t prepared,” said Green. “They looked surprised at the crowd. They told us what they had done, and what they would do…they didn’t provide us much information for questions asked. You had angry citizens, just now finding out.”

Repeated questions on health impacts of the site’s toxins, residents’ most urgent concern, were declined by EPA. The agency tests for contaminant levels but not health effects. Therefore, representatives deferred to HHS, but HHS had no response. One insistent questioner was spoken to on the sidelines by an HHS representative and given a community health survey, reported Renaud, who read it.

“It had a single question, but no direct questions about effects related to toxic exposure.”

Residents’ frustration fueled the determination of Green, Derrough and a growing number of supporters to push for full public disclosure, cleanup funding and thorough water and wildlife testing for toxins.

It will be a wait.

EPA’s sampling plan is expected to be done sometime this year. Then testing and damage evaluation begins. Even so, only 4 percent of the National Priority List sites evaluated are selected for remediation, states EPA’s website.

If Lane Plating is selected, it may be two to four years before any cleanup. That depends on funds. The excise taxes that originally supported the Superfund Trust Fund elapsed in 1995.

“A couple of times in the past Congress set aside funds,” Renaud noted. “This EPA says cleanup of toxic sites is a top priority…but the EPA budget has been cut under the Trump administration.”

Green organized the Highland Hills Community Action League, which met this week at Holy Cross Catholic Church on Ledbetter Road.

Green and Derrough hope to attend a lobbying workshop in Washington, D.C. and lobby for Superfund moneys. That is, if the current federal government shutdown doesn’t cancel the event.

“Superfund action really depends on support,” said Reynaud. “Support from the public and from elected representatives.”

Stay up to date on everything green in North Texas, including the latest news and events! Sign up for the weekly Green Source DFW Newsletter! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter.