A xeriscaped front yard in Fort Worth. Photo by Julie Thibodeaux.

In this episode of the Texas Green Report podcast, Marshall Hinsley talks to author Doug Tallamy about how the work of maintaining the essential ecosystem services that we all depend on must be taken up by every single person inhabiting the planet.

In this episode of the Texas Green Report podcast, Marshall Hinsley talks to author Doug Tallamy about how the work of maintaining the essential ecosystem services that we all depend on must be taken up by every single person inhabiting the planet.

From flood control and keeping pollinators thriving to protecting the plants that produce the oxygen we breath and mitigating the rise in average global temperatures all comes down to every single person on the planet learning to live in a more responsible relationship with the natural systems that sustain us.

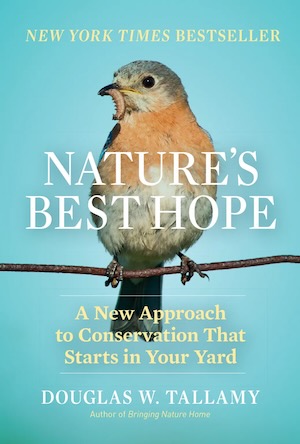

Doug Tallamy is the T. A. Baker Professor of Agriculture in the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware, where he has taught for over 40 years while authoring more than 100 research publications. He's written several books, including New York Times bestseller Nature's Best Hope, released by Timber Press in 2020.

The Texas Green Report is a production of Green Source DFW.

DOUG TALLAMY: Who's monitoring the quality of the ecosystem where you live on your property? It's you. That makes you nature's best hope

DOUG TALLAMY: Who's monitoring the quality of the ecosystem where you live on your property? It's you. That makes you nature's best hope

MARSHALL HINSLEY: Your yard as part of the food web, how we all need to learn to live with the insect world, and how our lives depend on our local ecosystems. A conversation with entomologist and author, Doug Tallamy, in this episode of the Texas Green Report, a production of Green Source DFW and the Memnosyne Institute.

I'm Marshall Hinsley.

MARSHALL HINSLEY:

Doug Tallamy is the T. A. Baker Professor of Agriculture in the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware, where he has taught for over 40 years while authoring more than 100 research publications. He's written several books, including New York Times bestseller, Nature's Best Hope, released by Timber Press in 2020.

He's also co founder of Homegrown National Park, an online resource for a grassroots call to action for everyone to join together to regenerate biodiversity and protect the essential life sustaining services that ecosystems perform for all of us.

According to Tallamy, we are at a critical point of losing so many species from local ecosystems that their ability to produce the oxygen, clean water, flood control, pollination, pest control, carbon storage and other ecosystem services that sustain us will become seriously compromised.

Dr. Tallamy, what is your message?

DOUG TALLAMY: Oh, you know, I have lots of messages. The main one is, we have a serious biodiversity issue on this planet. We've got two crises. We've also got a climate change crisis, but we've got a biodiversity crisis.

We've got two crises. We've got a climate change crisis, but we've also got a biodiversity crisis.

And if we had no climate change crisis, we would still have a biodiversity crisis. And it's a crisis because it is biodiversity. It is plants and animals that run the ecosystems that we humans depend on. So it's not just sad that things are disappearing. It's something we have to absolutely stop.

So my message is, we're in the Sixth Great Extinction event now. There is something we can do about it. Everybody — everybody — not just tree huggers, has a responsibility to be a good steward of their local ecosystem. And then I basically tell people how to do that.

Everybody — everybody — not just tree huggers, has a responsibility to be a good steward of their local ecosystem.

FOUR THINGS ALL YARDS MUST DO

MARSHALL HINSLEY: So what is the urban dwelling information specialist or nurse at the hospital, what is their role in this?

DOUG TALLAMY: Well, their role would be to make sure that any property they own, and we'll talk about people who don't own property in a minute. But if you own any property, you have to make sure it's doing four things. Every property has to manage the watershed in which it is. Every property is in a watershed and the way we landscape that, that property will determine how well that watershed performs.

Every property has to support a complex community of pollinators, primarily native bees. Not because they're pollinating agriculture, but because they're pollinating 80 percent of all plants and 90 percent of all flowering plants. So it's not, you know, the message we get from the media is we only need pollinators near agriculture.

If you own any property, you have to make sure it's doing four things: supporting the watershed, supporting a complex community of pollinators, supporting a food web and sequestering carbon.

Not true. We need pollinators everywhere we need plants. Every property has to support a food web. In other words, you've got to have plants in your property that pass on the energy they attract from the sun, turn it into food. If they don't pass it on to animals, we have no animals, and then you have no ecosystems, and you have ecosystem collapse.

And the fourth thing every property has to do is sequester carbon. Pull as much carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere as possible and lock it up in plant tissues. And then those plants actually pump extra carbon into the ground, into the soil. And that's why our soils are brown or black. It's because of carbon that plant roots have deposited there over the eons.

So those are the four things that every property has to accomplish if we're going to reach a sustainable relationship with the natural systems that sustain us. So, if that nurse or that information specialist owns a piece of land and look at that land and say, Am I doing this? How well am I supporting the watershed?

How many pollinators am I supporting? How much food am I passing on through the plants I have in my yard? These things are all determined by the choice of plants that you have in your yard. Also, largely by the amount of lawn that you have in your yard because lawn accomplishes none of those things. And these are decisions that every homeowner, every property owner can make to enhance those four goals.

How many pollinators am I supporting? How much food am I passing on through the plants I have in my yard? These things are all determined by the choice of plants that you have in your yard. Also, largely by the amount of lawn that you have in your yard because lawn accomplishes none of those things.

If you don't own property, if you live in an apartment or something, there's still something you can do in the way of container gardening. Most everybody in an apartment building does have a balcony or porch, and they can put containers that have the plants that are accomplishing the things we just talked about.

Now, admittedly, they'll have less of an impact than somebody who's got two or three acres. But imagine an apartment building where everybody had their balcony loaded with productive native plants that are going to support the pollinators, the migrating monarch, and all of that. To a foraging bee, that would be a wonderful resource instead of just this big pile of bricks that offers nothing.

So there's something that everybody can do. And also, if you don't own property, you can help somebody who does. You can volunteer. Help a land conservancy, help a park or preserve. They are all underfunded, they're all understaffed, and they will love you as a volunteer. So everybody can contribute to this quite urgent global need.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: It seems that your message on putting plants out to become part of the food web is kind of counter to the advice that the garden center gives, or that the tag on a particular plant might say something that's pest free. What are your thoughts about that?

DOUG TALLAMY: Well in the past we viewed plants, our ornamental plants at home, as decorations. Because they're pretty, and they are pretty. They are decorative. But they're so much more than that. The real trick is to reach a compromise. Where you have pretty plants that also share part of that energy. The idea that everything that eats a leaf is a pest makes no sense. Because, I met a woman in New Orleans, Tammany Baumgarten, several years ago.

In the past we viewed plants, our ornamental plants at home, as decorations. Because they're pretty, and they are pretty. They are decorative. But they're so much more than that.

And she suggested that we all take 10 steps back from our plants and all of our insect problems disappear. And that's because the only time you see the little bit of damage that insects are doing is when you're right up close staring at the leaf. So the idea that if you have a landscape where none of the leaves have been eaten at all, it is a completely dead landscape that's not accomplishing any of the things that we all need to do.

So, you know, it's a choice. Do we want pretty landscapes or do we want a healthy planet? And some people would choose pretty landscapes, but I choose the healthy planet.

EVERY YARD MUST CHANGE

MARSHALL HINSLEY: It seems that in so many places, though, that people live, the environment has been so disturbed that it almost seems insignificant whether this yard or that balcony has a plant.

DOUG TALLAMY: That's exactly why every yard and balcony has to change things. Let me give you some examples from our yard. Now we have 10 acres. It was part of a farm that was broken up, but it was mowed for hay. There was just about nothing here. We have put the plants back. My research at the University of Delaware has shown that if you count the number of moth species that are living in a particular place, they're part of that local food web.

And the reason we choose moths is because they produce the caterpillars that transfer more energy from plants to other animals than any other type of insect. So if you count the number of moth species, it gives you a good index of how productive and how stable the food web is that you have created on your property.

If you count the number of moth species on your property, it gives you a good index of how productive and how stable the food web is that you have created. The reason we choose moths is because they produce the caterpillars that transfer more energy from plants to other animals than any other type of insect.

Well, I've been doing that for the last five years. I've been taking a picture of every species of moth that is now making a living at our house. And they weren't before. It was practically bare soil. And I'm up to 1,199 species so far. I added three species this week. So it works. You can put it back.

It's not insignificant. And I know that people say, well, you've got 10 acres. It won't work on smaller properties. But we've got good data from properties like .6 acres. They've recorded, what is that, 149 bird species so far. One tenth of an acre in Chicago has recorded 123 bird species.

That are using their yard because they put the plants back. So there's very good evidence that it does work even on small properties. And it will work better if everybody gets together. If you're the only property in a city that does it, you're right. It's not going to work. But if everybody in your block does it, one tenth of an acre all of a sudden becomes two or three acres.

So it becomes cumulative. This is why we call this a grassroots movement. It's something everybody's gotta participate in. Or the more people who do, the more effective it will be. We're trying to change the culture. [It’s a movement] that recognizes that nature's not optional. It's disappearing. It is time to act.

This is why we call this a grassroots movement. It's something everybody's gotta participate in. Or the more people who do, the more effective it will be. We're trying to change the culture. [It’s a movement] that recognizes that nature's not optional. It's disappearing. It is time to act.

Once it does disappear, it's too late, and then we will disappear as well. But there's time to do it, and it bounces back. Nature's very resilient if we put the plants that support it back.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: What are your thoughts on the notion that that's why we have national and state parks? They're there to protect the species, to be a sort of a haven or a refuge for various species.

DOUG TALLAMY: Right. That's actually not why national parks were established. They were established because they were beautiful places. They were established so that future generations could enjoy them. That's a quote from Teddy Roosevelt. So really they were pretty places that humans could play in, but they certainly did perform critically important ecosystem services.

And that's true for all the parks and preserves we have around us. But we are still in the Sixth Great Extinction event the planet has ever experienced, which means they're not working. It's not enough. They're too isolated. We only have, what is it, 12 percent of the U. S. that's in some kind of formal park system.

That's 88 percent that is not. And most of that 88 percent is private property. So what we need to do now is practice conservation outside of parks and preserves on private property. That's the only option. We had this notion that humans and nature can't coexist. That's killing us. It's certainly killing everything else, but it's going to kill us as well.

12 percent of the U. S. that's in some kind of formal park system. That's 88 percent that is not. And most of that 88 percent is private property. So what we need to do now is practice conservation outside of parks and preserves on private property.

So we need to, we need to toss that. We need to find ways for nature to thrive in human-dominated landscapes. [It’s] certainly thriving at my house. But it could be thriving in dense neighborhoods as well.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: Are we currently seeing any consequences of not having taking this approach to our landscapes in urban areas or even in in rural areas?

DOUG TALLAMY: We certainly are. We've got global insect decline. We've lost 45 percent of the insects on the planet. And they are the little things that run the world, according to E.O. Wilson. We've lost 3 billion breeding birds in the U.S. in the last 50 years. That's a third of our bird population already gone. There is hardly a statistic about the abundance or diversity of any form of biodiversity you want out there that is not really, really bad news. So we don't need to document that the things are disappearing and that we have a problem here anymore.

It's documented. We need to act. We need to turn it around. We need a lot more statistics about how many things have rebounded after we put plants back. That's positive reinforcement, encourages people to, you know, to act even more. You know people approach this as if it's a sacrifice.

So we don't need to document that the things are disappearing and that we have a problem here anymore. It's documented. We need to act. We need to turn it around.

It's not a sacrifice. It's enormously rewarding to discover, to find new things that are using your property every day. If you have kids, what a wonderful way to introduce them to the natural world, to train them to be good stewards themselves. Right now, if they listen to the media, all they hear are negative things about nature.

It’s going to kill you in one way or another. It's something you should be afraid of. The murder hornet, all these things we hear in the media. No wonder people are afraid to go outside. We've got to turn that around. Nature's a wonderful, wonderful thing. It's extremely healthy.

There’s all kinds of studies now that show that any exposure to nature at all, amazingly small, short periods of exposure, lowers your blood pressure. It lowers your stress hormone, your cortisol. And when you lower stress, you end up performing all of the other tasks better. You learn better, you have better relationships, there's less crime.

Everything gets better when we're all less stressed. So you know, exposure to trees does that. So, this really is, it's a no brainer if we just look at the data that's already out there.

WHAT'S BUGGING YOU?

MARSHALL HINSLEY: You're no fan of mosquito foggers, are you?

DOUG TALLAMY: Well, mosquito foggers are doing exactly the opposite of everything I'm talking about. And they're doing it with misinformation. So they say — it's a booming business, by the way, around the country. People, we don't like mosquitoes. Most of the mosquitoes we don't like, by the way, are invasive species themselves. Aedes aegypti, it was brought over from the Middle East. Many of these species were the Asian tiger mosquito. They're a pain in the neck. They're a pain in the arm. I get that.

But trying to control them in the adult stage doesn't work, and we know that. So the mosquito fogging companies say this is a natural product, so it's okay. As if it doesn't matter that we're spraying it all over the place. It is a natural product, but so is cyanide. So that's not a viable argument.

They also say it only kills mosquitoes. That's just plain misinformation. It kills all the insects it comes in contact with, including monarchs. Two years ago, there was a big monarch kill. Hundreds of dead monarchs on the ground when they flew through mosquito gel. The important thing is, it doesn't control mosquitoes.

It's very hard to control mosquitoes in the adult stage because you have to kill 90 percent of them to do that. These fogging companies kill between 10 and 50 percent, which means they have to keep coming back and back and back and charging you each time. And in the meantime, they're killing all your pollinators and all the beneficial insects that we're trying to, you know, run our ecosystems with.

There is an alternative, and that's controlling mosquitoes in the larval stage. Everybody can do it on their own. You don't have to hire anybody. You just use mosquito dunks, which is, it's a biocontrol. It’s bacillus thuringiensis that you can buy at the hardware store. It's a natural bacterium that you put in a bucket with water and mosquitoes lay their eggs in the bucket.

And the larvae hatch and eat your little mosquito dunk and then they die. It's extremely targeted. It only kills aquatic diptera. And the only aquatic diptera in your bucket is a mosquito. So if everybody did that instead of hiring Mosquito Joe, we'd actually control mosquitoes and we wouldn't be killing everything else.

Mosquito fogging kills all the insects and doesn't control the mosquitoes. You control mosquitoes in the larval stage. So you've got to give up that stuff.

TREE GROVES

MARSHALL HINSLEY: What are some of the other differences that a yard that you design, as far as the landscape, would have, as opposed to current practice, for example, I know you've mentioned a three-foot center for planting trees.

DOUG TALLAMY: Okay, yeah, that's another problem that we have is our trees blowing over and crushing our houses.

And as we get more and more extreme weather events, that's happening more and more. And one of the reasons it happens is that we plant every tree in an urban or suburban setting as a specimen tree. We want it to be isolated so that it can reach its full grandeur over the years. Not compete with light or water with any other tree.

But that means when you get a lot of rain and wind, boom, over it goes. There's nothing to lock those roots in place. Trees don't grow that way in the forest. In the forest, they grow close enough together that their roots are interlocked with a very stable matrix. So you know, if a tornado comes, it'll snap them off, but it won't blow them over when they're interlocked with a number of other trees.

So I suggest creating tree groves. Don't ever plant an isolated tree. Plant two or three together — much closer than you would think you normally would. And plant them small so that they can grow up and interlock their roots, and then they will be much more stable and not blow over and hit our cars and our houses.

That way we increase the safety of our neighborhoods without sacrificing the trees. I hear a lot of people say, well, we're not going to have any more trees. You know that is not an option for the way ecosystems work around here. So let's find ways to have them more safely and planting a little tree grove is a good way to do that.

REDUCING LAWN SIZE

Another thing I talk about all the time is reducing the area that's in lawn. We mentioned the four things that every landscape should accomplish. Well, lawn doesn't accomplish any of those, and we've got 44 million acres of lawn in this country. That's an area the size of New England. And it's really dedicated to an ecological deadscape.

The reason we do that is because lawn is a status symbol. So, okay, I'm not suggesting we get rid of lawn. I'm suggesting we reduce the area that's in lawn. Let's aim for cutting it in half. That would give us 20 million acres. We could put plants back right where we live. And that's where I got the notion of creating a homegrown national park.

The lawn is a status symbol. I'm not suggesting we get rid of lawn. I'm suggesting we reduce the area that's in lawn. Let's aim for cutting it in half. That would give us 20 million acres.

We could restore 20 million acres right in our residential neighborhoods, and that would be an area bigger than all of our major national parks combined. It's easy to reduce the area of lawn. Just start planting trees and putting in some beds.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: How do homeowners associations take to your propositions?

DOUG TALLAMY: They're coming around. We started a lot of these communities, gated communities, as far back as the 70s. And right away, they wanted to set rules to make sure we don't have rusty cars in our front yard. We're a high-class neighborhood, and we're gonna have rules that display that all the time.

And that all made sense. But then they started going crazy with landscaping rules about which plants you could have and how often you had to mow the lawn. And it was all about this high status aesthetic, which really goes directly against the ecological functions that our landscapes have to perform.

So that was a mistake. It was an overstep. They were starting to realize that. And a lot of them are coming around. There was a lawsuit in Maryland last year. Where the homeowner actually sued his HOA, said you cannot tell me that I can't do this or that, and he won. So now there's a legal precedent that homeowner associations have overstepped.

The real way to go about this is to convince them that there are better ways to landscape that are not ecological dead zones, that are not smothered in pesticides and mosquito fog. They're healthier for us and certainly healthier for the ecosystems that support us. But it's another reason I say, don't get rid of the lawn.

You keep it. It's a cue for care. When you have less lawn, you can border the beds you put in your yard, border your sidewalk and your driveway with manicured lawn. And it shows that you understand what the status symbol is. You're just going to have less of it and you're going to have more plants on your property, and no homeowners association objects to that.

REWILDING

MARSHALL HINSLEY: How does the homegrown National Park Mission relate to the concept known as “rewilding?”

DOUG TALLAMY: There's all kinds of levels of rewilding. There are some groups that want to actually bring back relatives of the big Pleistocene mammals that used to be in North America. And that includes elephants and lions and camels. All right, that's one thing. I'd love to see us just take care of the things that are still here, like bison, like elk, like our predators, our wolves. These are things that helped run — our mountain lions — healthy ecosystems. There are big rewilding projects trying to connect the huge areas of northern Canada right down through the Rockies, and they're meeting with some success. Talking about extending them over to the Sierras in California. But on a lesser degree, you know, what we've done at our house here in Oxford, Pennsylvania — that's rewilding.

We've put the eastern deciduous forest back and created a whole lot of life. We've got 60 species of birds that breed on our property because we put the plants back. So we don't have any lions, tigers or bears, but we still have increased biodiversity many fold. And in my book, that is rewilding as well.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: I think the concept of rewilding that I'm most familiar with is where in a landscaping project or even in a larger municipal property, we pick a species and then we focus on creating a habitat for that species. And so then we plant food, shelter, plants and the like, that would sustain that species. And in view of that definition or that concept, what does Texas have, perhaps most importantly, as its resource of or as a species to focus in on rewilding?

DOUG TALLAMY: You know, when I think of Texas and the vital role that it plays in the monarch migration, that's the first thing that comes to mind. When the monarchs east of the Rockies migrate to Mexico, all the ones in the real east fly down along the Gulf and fly right through Texas, right through the Rio Grande Valley.

And when they're migrating to Mexico, they need forage all along the way. Forage is nectar, blooming plants. From late August, all the way through October. I remember several years ago, Texas had a terrible drought and there were no blooming plants, except in people's gardens where they had kept them watered.

And that was the only refuge for migrating monarchs. So monarchs took a big hit that year, but fortunately people had gardens that they kept blooming plants alive in. And it provided a vital resource for monarchs. But you've got, I mean you've got the golden cheek warbler in the Hill Country, which is — I don't know if it's officially endangered. I think it is. It's got a very small range. It likes the oak-cedar habitat. That it's the only place it's going to live. If you own property in that area, that's what I would focus on. This is called wildlife management. You've got rewilding, but it's really old time wildlife management where you manage for particular species and provide what they need.

And particularly a species that's in trouble. And by the way, the Monarch is now listed by the IUCN as an endangered species. You focus on those and almost always when you focus on a particular species or a particular group of species, you're helping other species as well. They become umbrella species.

So if you create forage and so-called monarch stations, milkweed patches for monarchs to breed, you're creating resources for many other insects and birds as well. I talked about monarchs getting down to Mexico in the fall, but then in the spring when they come up, they fly across the Rio Grande.

Where do they go? They go right through Texas. And what do they need? They want to start laying eggs in native milkweeds as soon as possible. I've been to the Rio Grande during that migration and you know you get to large parts of Texas and some of these big ranches there's not a milkweed in sight and those monarchs have to keep flying and flying and flying until they finally hit some.

So that would be a great rewilding project to start building the population up. As soon as they get back into the states, by tolerating milkweeds on the side of the road, putting patches aside. You know, when you own a ranch that's — I don't know, 30, 000 acres? — you can have a few patches of milkweed without too much of a loss there.

So it's usually just ignorance, lack of knowledge of what other things need that keeps us from doing this. But more and more people are doing it and, and we're seeing positive results.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: You've written that nonnative ornamentals support 29 times less animal diversity than native ornamentals. Is there any place for nonnative ornamentals?

Like, say — zinnias, marigolds, flowers that people plant or anything like that?

DOUG TALLAMY: The answer is yes. We did an experiment with chickadees. And long story short, you can have up to 30 percent of your woody plant biomass nonnative without destroying the local food web, as long as 70 percent is native making the insects that those birds need. So the assumption is — it's not an assumption. We've measured it a hundred times — that the nonnative plants are making, they're producing very few insects that drive the food web. But that suggests there's room for compromise. We can have a lot of these plants. You can have your crepe myrtle. You can have your ginkgo. You can have your camellias and they're not destroying the food web as long as you don't have too many of them. As long as you have important other species there with them. And oaks are the most important species in 84 percent of the counties in which they occur.

Marigolds, any of the nonnative flowering plants — as long as they're not invasive and most of them are not — provide nectar. And that's a very valuable resource for, again, for those migrating monarchs, and for any of the generalist bees that can go to a number of flowers. When we're planting pollinator gardens, we really want to plant for specialist bees.

Marigolds, any of the nonnative flowering plants — as long as they're not invasive and most of them are not — provide nectar. And that's a very valuable resource...So yes, we can compromise, we can have them, we just want to make sure that we've got the other native plants as well.

The generalist can use those flowers as well because specialist bees can only reproduce in the pollen of particular plants. It doesn't mean you can't have some zinnias around. It doesn't mean, uh, what's another good example? I don't want to say butterfly bush because that can be invasive. But these plants that make a lot of nectar, a lot of things do go to them.

Helps the honey bee, for sure. But we also want to make sure we have the plants that support those specialist bees, because we've got about 4, 000 species of native bees in this country, and over a third of them can only reproduce in the pollen of particular plants. If we only had zinnias out there, we'd still have some generalist bees, but we'd lose all of the specialists.

So yes, we can compromise, we can have them, we just want to make sure that we've got the other native plants as well.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: You mentioned native bees, and we know that's not the honeybee. Is the honeybee a competitor to native bees, or do they live in peace with each other?

DOUG TALLAMY: There is research that has gone back and forth on that and I think it depends —I’m sure it depends — on the quality of the landscape around these bees.

They're all competing for the same thing. They're competing for pollen and nectar. And of course, we give honeybees an unfair advantage because we supplement their food. We give them, you know, sugar and protect them during the winter and they develop these huge hives with thousands and thousands of individuals.

If there's only a few blooming plants out there, then all those individuals need to descend on them. Yeah, there's serious competition and our native bees lose because they're not there in those numbers at all. But if we had well-planted landscapes where you have a lot of forage, the way it used to be, then other studies have shown, no, they can't demonstrate any negative effects at all.

Honeybees don't go to all the flowers. They like particular ones more than others. And many of those specialist bees are going to flowers that honeybees won't, you know, won't spend a lot of time on. So there is room for coexistence, but all the bees, the honeybee and our native bees would benefit from getting more flowering plants out there.

And of course, the Lady Bird Johnson Society does exactly that. They do a wonderful job of that. So we want to spread that message and those practices as far and wide as possible.

TAKING RESPONSIBILITY

MARSHALL HINSLEY: Almost all the problems that we've talked about or that can be talked about in the ecosystem, they've been human caused. But in your book Nature's Best Hope you identify humans as nature's best hope. Can you speak a little bit about that?

DOUG TALLAMY: Sure. Well, you're right. We've caused these problems. So who's going to solve them? We are. We talk about the issue as having a grassroots solution.

Again, I'm focusing on the area outside of parks and preserves — they're usually regulated by the government or some bigger agency, not by individuals. But who's monitoring the quality of the ecosystem where you live on your property. It's you. That makes you nature's best hope. And it is an awesome responsibility.

So it's not that it's hard to do. The hard part is convincing people that it's necessary and that it's their responsibility. The reason I say it's everybody's responsibility is because everybody depends on the quality of Earth's ecosystems — of your local ecosystem. You depend entirely on that. So why wouldn't you share the responsibility of taking care of that ecosystem?

The hard part is convincing people that it's necessary and that it's their responsibility. The reason I say it's everybody's responsibility is because everybody depends on the quality of Earth's ecosystems — of your local ecosystem. You depend entirely on that. So why wouldn't you share the responsibility of taking care of that ecosystem?

And if you say, well, you know, I don't want to do that. Okay, then hire somebody who will. Now that's an entire new industry that can really expand. A lot of older folks don't want to be out doing this, but rather than hiring the mow-blow-and-go guys that are going to continue to destroy local ecosystems, hire the ecological landscaper who's going to put it back together again.

It's our responsibility. We say we own a piece of the earth? Right, then you own the responsibility of taking care of it. That's why I say you are nature's best hope.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: What are resources people can go to to find out more about planting natives? Where to find the plants to even purchase in the first place?

DOUG TALLAMY: We've created a tool on the National Wildlife Federation website called Native Plant Finder, where you put in your zip code and the ranked list of the best woody and herbaceous plants for your county will pop up. There's a second tool on that website as well called, Keystone Plants by Ecoregion, and this one is not by county.

So nature doesn't follow political entities. Nature follows soil type and temperature and altitude and latitude. So there are things called ecoregions, where all of those things are similar. And this website is created at ecoregion level one, which is very general. We've got to move it to ecoregion level two.

But you can go to the website and it will tell you all of the — not just the woody plants that are supporting the keystone, not just what the keystone woody plants are — but it will also tell you what the best specialist pollinator plants are. And as far as I know, that's the only resource that provides that knowledge.

So you can go look at it, see what ecoregion you're in and what the best plants are for supporting those specialist pollinators. And then you know the next step is, where do you find these plants? How do you find out who's selling them? And that's much more regionalized. This is where I would turn to the Texas Native Plant Society.

It's a great resource. It's a very, very active society. You’ve got so many counties in Texas, but they will direct you to the nurseries that are selling the plants that you're looking for. Probably better than any other resource.

The demand for native plants now outstrips the supply, but the industry is responding to that. You know, people think nurseries are only going to sell nonnative plants. They just want to sell plants. What they have to do is be convinced that you want to buy native plants and they're getting that message.

So they're starting to carry more — higher numbers and more diversity. So you know this is where the market system is actually starting to work.

LEAVE THE LEAVES

MARSHALL HINSLEY: Raking the leaves. Fan or not a fan?

DOUG TALLAMY: I want to keep all the leaves that fall on your property on your property. We will have to move them around a little bit. When they fall on the lawn that you're going to keep, you have to get them off the lawn. Raking is far better than mowing them because that chops them up and in those leaves are an awful lot of living organisms.

There are 70 species of moths — important components of the food web, that eat dead leaves, believe it or not. So what we want to do is we want to create beds underneath all of our trees. And the mulch under those, in those beds, should be the leaves from that tree. Those leaves contain the nutrients that that tree used the year before. And the nutrients need to break down and go to the soil and then the tree can take them up again in future years.

There are 70 species of moths — important components of the food web, that eat dead leaves, believe it or not.

There are more species living in the soil that break down those leaves than there are above the soil. So it's a really important part of our ecosystem. It's underappreciated because we don't see it. And those species are all really tiny. So the leaves make a nice blanket. They protect the moisture of our soil.

And of course, in Texas, that's really important when you go through your dry periods. Bare soils — it's an ecological no-no — because it gets sun baked, it kills the mycorrhizae?, it gets washed away by that sudden thunderstorm, wind erosion. Nothing good about bare soil. So we want it covered with mulch and the dead leaves from the previous year are a great mulch.

And even better than mulch is living plants. So any kind of ground cover that is protecting the soil and the leaves within that ground cover are really valuable. Yes, we're going to get the leaves off the lawn because that lawn, remember, is a cue for care. We're going to keep it manicured. The neighbors will be happy. But a little bit of raking will push them around to where they can make it through the winter without any problem

There are 70 species of moths, we call litter moths that only eat dead leaves. The banded hair streak — it's a beautiful butterfly —the larvae develop on dead leaves.

In a single square meter of healthy leaf mulch, there's 250,000 mites; 100,000 springtails, little collembolas, primitive insects; 90,000 proturas, which are even more primitive insects. A million nematodes. That is where the firefly larvae live as predators, feeding on the things that eat leaf litter.

In a single square meter of healthy leaf mulch, there's 250,000 mites; 100,000 springtails, little collembolas, primitive insects; 90,000 proturas, which are even more primitive insects. A million nematodes. That is where the firefly larvae live as predators, feeding on the things that eat leaf litter.

So it's an extremely active biological zone. And when you rake it all away or chop it up or burn it, you're throwing all that away. You know, the average lifespan of an oak tree is 900 years. You can say, well, they never lived that long. That's right. That's because we rake the leaves the way that they need every year. They do that for 50 years. And of course you're starving the tree over long periods of time. We chop up their roots. We do all kinds of things. But leaves are a critical component of our ecosystems.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: If we reduce our lawn space and we're leaving the leaves in place, what is the average homeowner going to feel accomplished doing on a Saturday afternoon?

DOUG TALLAMY: You mean if they don't have to go out and mow?

MARSHALL HINSLEY: Are you advocating for lazy sleeping in on Saturdays?

DOUG TALLAMY: Oh my goodness. Well, first of all, these landscapes are not maintenance free. So I would say spend that Saturday afternoon thinking about what else you can do to your property or just go out and enjoy it. Start counting the number of birds you see using your property or the number of butterflies that you see.

These are enjoyable things and to me it's productive. It's a lot of fun at my house to record a new species we've never seen before. Doesn't take a lot of work to do that. But enjoy the fruits of your labor. Nothing wrong with that.

SEEING CHANGE

MARSHALL HINSLEY: So from a traditional, fully lawned yard to a yard that's more like you're describing, how soon in the process of conversion would someone begin to see a difference in the wildlife?

DOUG TALLAMY: Right away. I’ve got pictures of oak trees that I planted as acorns. The very first year, they're about three inches high. I've got a picture of a caterpillar on the ground eating the leaves of one of those trees, of pin oak, which means that tree's contributing energy to that food web in the very first year.

Now I have that picture because then I went out and looked for it. I also have a picture of a white oak I planted in my front yard. It's about three feet tall. And in the very first crotch of branches where they split out, there's a field sparrow nest. So wildlife will start to use these plants right away, particularly in an area where you don't have very many resources.

When you create the only game in town, they're all going to come because they're desperate for, for these different plants. So it doesn't take long at all, but it keeps building. That's why I say I keep finding new species of moths at our house because they keep coming.

Because our property is maturing. It's only, at this point, it's 22 years old, which might sound like a lot of time but in ecological time, that's not much time at all. And those acorns I planted are now, those are trees that are 60 feet tall. So things really take off. And as I said before, it's a lot of fun.

DISAPPEARING PRAIRIE

MARSHALL HINSLEY: Much of Texas was previously prairie. What destroyed the prairie? Is it all the roads, homes and parking lots we've built?

DOUG TALLAMY: Yeah, But originally it was farming and grazing. Of course, you know, where it was simply too dry to farm, we put cattle on all those landscapes.

Not only did we do that, we brought in nonnative grasses to support those European cattle. Things like cheatgrass, which is a major invasive species at this point, responsible for a lot of the fires that we have in the West. So it changed the nature of these prairies. Cheatgrass, for example, has a a burn schedule of about once every two years.

When that invades an old shortgrass prairie or even a sagebrush community, it'll still burn every two years. And it kills all those other plants because they've got a 30- or 40-year burn schedule. So the grazing, the rangeland that we created throughout certainly much of Texas was another major factor.

It wasn't simply plowing it up. Then, when agriculture started to die off in developed areas, then we put in the housing developments and the shopping centers and everything else. But largely the prairie was gone at that point. It was some form of agriculture.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: To what extent is the Great American Lawn a culprit?

DOUG TALLAMY: Well, the Great American Lawn is a status symbol. We've got 44 million acres of it. It's an area bigger than the size of New England. It's an ecological deadscape. So what you do is you take out all the native plants that were there and put in cool season European grasses, and you mow it, and you put fertilizer on it with broadleaf herbicides.

It's an ecological deadscape. Again, the lawn came in after most of the prairies were actually destroyed. But it persists. It’s an enemy of regenerating these prairies. Because now we've got this idea that humans and nature can't coexist. You can't have these native plants in your yard because it's not part of the culture.

The Great American Lawn is a status symbol. We've got 44 million acres of it. It's an area bigger than the size of New England. It's an ecological deadscape.

And that's where pocket prairies come in. Because, you know, there are ways to do it in ways that are culturally acceptable. But you always have to have your eye out for that neatness value that's very much a part of our culture, part of that status symbol. What I've been trying to champion for the last many years is to not get rid of lawn, but to reduce the area that's in lawn.

If we could cut the area of lawn in half, that would give us more than 20 million acres to put towards conservation right where we live. And that's where that notion of Homegrown National Park comes from. Because we could, we really could create the biggest park in the country if we restored at least half of the area that's now in lawn.

And if we put some of it back into little pocket prairies — prairie-type habitat — get as many of those plants back into the system as possible, there's so many benefits there. Real prairie plants have deep roots. Very deep roots. Deeper than most trees. Because they're going down to tap into moisture that's down deep.

Those roots are pumping carbon into the soil every day. So even though they're not huge plants compared to a tree, they are really important in terms of carbon sequestration. So any place you can remove lawn — which is not sequestering any carbon, because its roots are very short and we mow it all the time, releasing any carbon that it's grabbed — with prairie plantings, you are helping climate change. Now it's true when you plant a tree as well, but when you move past the area where trees belong, prairie's a wonderful way to do that. So simply from an aspect of fighting climate change, of managing our watersheds, of supporting pollinators, of supporting food webs, those prairie plantings are really, really important.

When we're talking about reestablishing food webs — and by that I mean putting plants in that are willing to share the energy they've captured from the sun with other creatures. Now, it usually starts out with insects — things like caterpillars and grasshoppers — and then all of your pollinators. We've got 4,000 species of native bees in this country that did all the pollination before we brought honeybees over.

And many of them are specialists in that they can only reproduce on the pollen of particular plants. So if you have those plants in your yard, things like goldenrod and asters and perennial sunflowers — those three genera alone will support over 40 species of bees that won't be there if you don't have those genera.

So you get to rebuild the pollinator community. And it's important to understand why we need pollinators. You hear all the time you need them because they pollinate a third of our crops. And I hear people say, well, I don't live next to a farm, so I don't need any pollinators. It's actually about a twelfth of our crops that they're pollinating, and I don't like that argument because they're so much more important in terms of the greater ecosystem.

They're pollinating 80 percent of all plants and 90 percent of all flowering plants. So if we lost our pollinators, we'd lose 80 to 90 percent of the plants on the planet. So when you put in any kind of a prairie planting in your yard, you are helping maintain the creatures that keep us alive on this planet. It's really, really important.

And yes, they're sequestering carbon. And yes, they're managing the watershed because those deep root systems create channels where the water infiltrates and replenishes the water table as opposed to running off in sheets when you have a thunderstorm, which is what happens with lawn grasses. And then finally those plants, by making those caterpillars and those grasshoppers and the other things that are eating those plants — are providing the food that supports other animals.

Let's just talk about birds. If you want a Carolina chickadee breeding in your yard, you need 6,000 to 9,000 caterpillars just to get the babies to the point where they leave the nest. That's one nest. Where are those caterpillars going to come from? They're going to come from the plants in your yard, and it's not lawn, and it's not nonnative trees. It's not crepe myrtle. It's not camellias. It's not all these plants we bring in from Asia.

It's going to be the native plants. And again, things like goldenrod support a 110 species of caterpillars. So that's what I mean by rebuilding the food web so that you can have other living things in your yard. And those are the things that run the ecosystems that support humans. Our life support systems come from, from healthy ecosystems, and we're destroying them everywhere.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: I'd like to emphasize what you just said because it seems counter to what everybody thinks a landscape needs to be. We need to create landscapes with the intention of them being eaten.

DOUG TALLAMY: That's right. If you have a plant that is not being eaten by something, it's not doing its job. It's captured energy from the sun, turned it into food for animals, but not shared it. So then, you know, if all plants did that, we'd have no animals on the planet. Including us.

So you want a plant that's going to share it. Having things in your garden — living things in your garden, other than the plants — means you've got a healthy garden. If you don't have that, you know, that's an entirely different approach from what we had just a few years ago, where you didn't want any insects, no “pests,” nothing in your garden.

It was just a decoration. Now we're looking for pretty plants that are also ecologically functional. And that means you've got to share that energy with other living things.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: People who try their hand at gardening and know that I grow vegetables often ask me how to get rid of bugs, and my response is, you don't. I try to let the ladybugs take care of the aphids, and the spiders keep down everything else, but that means that I have to put up with a population of aphids, and a population of grasshoppers, and other so-called pests, or I won't be able to keep the predators around.

DOUG TALLAMY: That's right. You know, predators are not going to be around if there's no prey, and that's the problem with insecticides. If you kill off the prey, first of all, the predators and the parasitoids, the things that actually keep your pests in balance, are much more sensitive to insecticides than the herbivore, the aphids and the other things are.

So the very first things that die are the things that you want most in your garden. And then you have none of them, and the aphids will recover very quickly, so you have no natural controls. So yes, you need some prey items – call them pests — whatever you want, in order to maintain the predators that keep them in balance.

Which means we have to tolerate other living things in our garden. As opposed to, you know, having it, this picture perfect postcard with not a single leaf disturbed. That's not what a living system is. I hate the word pest. You need the prey for the predators.

They need to have something to eat their entire lifecycle. So what we're really saying is you need all the trophic levels — you need the plants, you need the things that eat the plants and you need the things that eat the things that eat the plants. You need all of them all the time. That's a balanced ecosystem.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: And if you look at aphids in an ecosystem, there are other insects that actually rely on their secretions, which we call honeydew.

DOUG TALLAMY: Particularly ants. I mean, they're the big ones. Remember ants are predators. So by having aphids that get the honeydew, you're supporting ant colonies that then will eat a number of other things. It's all part of the, it's a very complex system. So, it's not, you know, one species and another species.

It's dozens of species interacting with each other. I get the question all the time — what is this particular species good for? And the answer is that the more species that are in our ecosystems, the better that ecosystem functions. And every time you lose one, no matter what it is, it produces fewer ecosystem services, less life support for everything, but including humans. So the loss of any species is a detriment to an ecosystem. And the gain of any species is a benefit. So just look at, look at the entire system, not focus on one species at a time.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: I once wrote about goldenrod and a professor contacted me asking me to be on the lookout for goldenrod gall. He can't find it anywhere.

DOUG TALLAMY: I've got a bunch in my yard.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: Oh, okay. I guess he can't find it in Texas or maybe not where he has looked. That's interesting.

DOUG TALLAMY: So the goldenrod gall —there’s actually two kinds. The round one is formed by, it's a fritted fly. So and that's an ex?> It's actually a valuable source of food for chickadees and tip mice and other birds. Downey woodpeckers during the wintertime because they'll peck open those galls and eat the fly larvae that's over wintering in it. And then there's a, a more elliptical gall, which is made by a moth and the same thing — the caterpillar is in there. And things will pick it open and have something to eat during the winter time.

Getting your birds through the winter is important because, you know, if they die in the winter, you don't have them in the spring. Now we supplement by putting up bird feeders all the time, and that's great, I support that. But if we had the plants — in the old days there were no bird feeders and they relied on the seed and the insects that remained in our gardens over the winter to make it through the winter themselves. And the goldenrod galls are an important component of that.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: Fascinating on goldenrod gall. I didn't know that. I figured something ate them, but I hadn't found that yet. One thing that I think is, when we kind of return to the topic of pocket prairies, we were looking at maybe a four by four plot of land or a strip along a sidewalk or a walkway or something like that. And we can't recreate the entirety of the prairie ecosystem in such a small plot. But one thing you mentioned that I thought was interesting was to sort of pick a species and plant — specifically host plants for insects that you want to bring back.

DOUG TALLAMY: Of course, a monarch is the perfect example of that. You're only going to develop monarchs on milkweeds. So you've got to have the milkweeds to do it. And I get calls, people say, I planted a milkweed. And worms got on them and ate it, so I squished the worms. Well, the worms, of course, are caterpillars of the monarch.

But a single milkweed ramet is not enough to get even a single caterpillar through to maturity. So what you really want is a milkweed patch. Then you can have all the monarchs you want, and there'll be enough food material so they can complete their development. So it's a balance, a delicate balance between diversity.

You want as many species as you can get, but you want enough of each species so that the things that need those plants can actually complete their development. There are a number of butterflies that depend on asters. But a single flowering aster is not going to be enough to support any of them.

When you are trying to support pollinators, than you want to make their foraging as efficient as possible. So you want a number of blooms of the same kind, very close to each other, so that they don't have to fly a hundred yards in between each flower. That burns up more energy than they get from the nectar and the pollen.

So patches of plants are very important. We do want diversity, but you need density as well. You need abundance.

When you are trying to support pollinators, than you want to make their foraging as efficient as possible. So you want a number of blooms of the same kind, very close to each other, so that they don't have to fly a hundred yards in between each flower. That burns up more energy than they get from the nectar and the pollen.

POCKET PRAIRIE

MARSHALL HINSLEY: What do you recommend then for anyone who wants to try to piece back together this ecosystem of the prairie with a pocket prairie in a yard, a schoolyard, something to that effect? What should they generally aim for or what practices should they adopt?

DOUG TALLAMY: I would recommend starting small so you get the feeling for what's going to be happy in your yard. This is where I would use lawn or grass as a cue for care. So line it with maybe one mower's width of turf grass that explains to your neighbors: this is not just a patch you forgot to mow. That it's an intentional part of your landscape. And it gives it aesthetic value even in the wintertime when not much is happening. But pick, you know, start with the common plants that we know we're going to do. Well, goldenrod is a perfect example of something you want to mass.

You don't want a single strand of goldenrod. You want a mass of it so that they will support each other. One of the complaints of a lot of our prairie plants is that they're tall and leggy and they'll fall over. Well, they evolved to grow in, you know, a big area with a lot of plants that support each other.

So think about that. Try to provide the support by having, you know, lots of structure there with a number of stems of the same type of plant. So that it's not floppy and falling all over the place.

But I would treat it as a hobby. You're contributing to conservation with this hobby. And you will learn what works and what doesn't work as you proceed. So I'll give a talk and people say, I'm going to go home and rip out all my lawn. I'll say, no, don't do that, you know. Replace a part of your lawn and figure out how to do it. There are lots of help groups, online groups that will, can walk you through this.

There's several books out there about how to make meadows and prairies. Making a meadow and a prairie is actually one of the harder things to do. It's very easy to plant a tree, but having a successful pollinator patch or pocket prairie, takes a little bit more knowledge and a little bit more effort.

And you don't want it so big that it's a big target for invasive species. These things are easily invaded by the plants we don't want. So learn what they are and then monitor. You know, they will invade. So you just, you have to watch it each year and make sure you pull those out.

It's going to tie you to the land. It's going to involve you in your own property. But you will see all the life that comes back to your little piece of property. It's very rewarding, It is our responsibility as gardeners of the Earth, it's our responsibility to make it a livable Earth.

So there's a lot to feel good about when you actually do this. And if you don't want to garden at all, hire somebody who knows how to do it. So that your yard doesn't remain a dead scape. That's a growing industry — ecological landscapers. All you have to do is hire them, just like your mow-blow-and-go lawn guys.

They'll come and they'll put in the plants you need and they'll take care of them. They'll maintain them and you don't have to do anything.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: Are pocket prairies and fertilizing and pesticide services that are offered by the week or whatever, are they compatible?

DOUG TALLAMY: No.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: People who have that in their lawn?

DOUG TALLAMY: No, and neither is mosquito fogging. Mosquito fogging kills all the insects and doesn't control the mosquitoes. You control mosquitoes in the larval stage. So, you've got to give up that stuff. Your pocket prairie does not want a lot of fertilizer. So give up on that too. Prairies do well in relatively poor soils. If they're over fertilized. What you're going to do is encourage a few thug species that'll take over.

So forget the fertilizer. And, you know, we're trying to bring the life back so we don't need the pesticides. And you certainly don't need the mosquito fogging. You're going to save a lot of money doing this.

STEWARDSHIP

MARSHALL HINSLEY: What am I too ignorant to ask you about?

DOUG TALLAMY: [Laughs.] You know what I always try to end up these discussions with, is stressing the responsibility that everybody on the planet has towards good Earth stewardship. Everybody — everybody in Texas, everybody in Dallas, everybody in a city requires healthy ecosystems.

It's not an option. Which means, keeping them healthy, taking care of them is everybody's responsibility. It's not just a few conservationists. It’s not just a few ecologists. Right now the system we have is — you've got your conservation biologist, you've got your ecologist —everybody else has a green light to destroy the planet. That makes no sense at all.

So I want people to accept their responsibility in being a good steward of the planet. If we're going to have the audacity to say, I own this piece of the earth. Alright, but you've got the responsibility to taking care of that. And how you do that? That's what we're talking about.

The pocket prairies, reducing your lawn and planting trees. All of those things is how you take care of it. But accepting that responsibility is our biggest challenge right now. Because most people don't realize that they have it. They thought that humans and nature don't coexist.

Accepting that responsibility is our biggest challenge right now. Because most people don't realize that they have it. They thought that humans and nature don't coexist.

Nature is happy someplace else. It's not happy someplace else. The only future model is that we do coexist because humans are everywhere. So accepting that and finding ways to make that work is the future. And that's what I always like to end these kinds of conversations with.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: Thank you, Dr. Tallamy.

DOUG TALLAMY: You're welcome. Thanks for the opportunity.

MARSHALL HINSLEY: I'm Marshall Hensley. Thank you for listening to this episode of the Texas Green Report. To discover more about the state's wildlife and wild places and the people who are keeping Texas wild and beautiful, visit TexasGreenReport. org.

Stay up to date on everything green in North Texas, including the latest news and events! Sign up for the weekly Green Source DFW Newsletter! Follow us on Facebook,Twitter and Instagram. Also check out our podcast The Texas Green Report, available on your favorite podcast app.