The sign of a member of Frisco Unleaded, a community group formed in Frisco to combat the Exide lead smelter in that city)

June 6, 2012

When Shiby Mathew and her family moved to Frisco in 2008, they didn’t know that one of their neighbors would be a lead smelter.

It wasn’t until Mathew was at her pediatrician’s office in 2010 with her two children that she learned about Exide Technologies, a battery recycling plant about two miles from her home.

Explaining that there were some concerns about the lead processing facility, her doctor suggested an in-office test on her children for lead. The facility was at the time under scrutiny for its high lead emissions.

When both of her children tested positive, Mathew suddenly found herself on the road to life as an environmental activist. By fall 2011, she was leading Frisco Unleaded, a grass-roots group whose goal became to shut Exide down.

(Photo: A flyer for the group Frisco Unleaded)

This week, Mathew and other Frisco residents who fought the facility, were celebrating after a city announcement that Exide would cease operations by the end of the year. After years of effort, this was an outcome thanks in large part to the effort of local citizens’ like Shiby Mathew.

The Exide plant’s history dates back to the 1960s, when Frisco was a small farming community of about 1,500 people. In 1969, Exide began recycling batteries, a process that involves melting extracted lead. Since then, the city has grown to more than 115,000, and the plant is now surrounded by schools, businesses and luxury homes. The facility came under fire in recent years when it planned to expand operations without notifying the city and was unable to meet new EPA standards. Residents concerned about the growing research linking lead exposure to health risks and learning problems started asking questions.

Like Mathew, fellow Frisco Unleaded member Eileen Canavan didn’t know about the possible dangers of living near the plant when she moved to the community in 2007. The company is still listed in the chamber director as a battery recycling center.

“I thought ‘recycling’ -- that sounds good,” she said.

She joined the movement for the first time last year after seeing a TV news report about the controversy surrounding the plant’s emissions. A lifelong Republican who supports big business and harbored skepticism about the EPA, Canavan suddenly found herself on the side of local environmental advocates opposed to the exide facility.

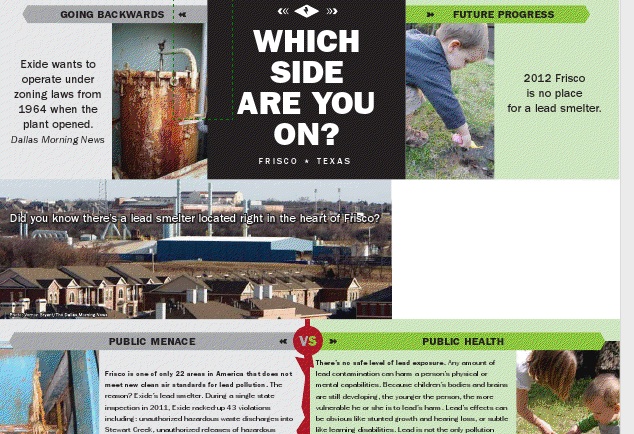

By that time, public activism was already underway. In April 2011, Joy West, a former Frisco city councilwoman, and Val Maso, wife of Frisco Mayor Maher Maso, had launched Get the Lead Out of Frisco, a group that oversees leadfreefrisco.com, a website to keep the public informed. The website published a map showing the dozens of daycares, businesses and schools that lay within a 5-mile radius of the plant. In August, Texas Campaign for the Environment began canvasing Frisco neighborhoods urging people to get involved. The agency collected nearly 1,500 comments from residents with concerns.

published a map showing the dozens of daycares, businesses and schools that lay within a 5-mile radius of the plant. In August, Texas Campaign for the Environment began canvasing Frisco neighborhoods urging people to get involved. The agency collected nearly 1,500 comments from residents with concerns.

(Photo: The website of leadfreefrisco.com, a clearinghouse of information on public health and other issues surrounding the Exide lead smelter in Frisco)

Frisco Unleaded formed soon after. With support from Texas Campaign for the Environment and Downwinders at Risk, a DFW-based environmental group devoted to air quality concerns, they helped keep the issue in the spotlight. Jim Schermbeck, director of Downwinders at Risk, advised them to shift their focus from pressuring Exide to comply with federal standards to shutting the plant down.

Members attended every public meeting, met with city council members and sent out flyers to homeowners.

In October, they hosted a canned food drive with a goal of collecting 2,000 cans, equal to the number of pounds of lead released from Exide’s smokestacks annually. At one public meeting, members, along with TCE staff, showed up wearing smokestacks on their heads.

Schermbeck believes their participation in the discourse influenced city leaders to take more aggressive action.

“There’s no doubt this group reframed the debate,” he said.

Frisco Mayor Maso said the city welcomed public involvement from groups like Frisco Unleaded as well as individuals.

“None of us are as smart as all of us,” he said. “We received a lot of feedback from residents. That helped us ask some of those questions and look at some of the angles.”

At the end of May, after initially starting a legal process to close the plant, the city announced an agreement with Exide to cease operations this year.

As part of the negotiation, the city of Frisco is purchasing 180 acres surrounding the facility for $45 million dollars, with the hopes of reselling part of it for commercial use and possibly developing it for municipal activities and a park after cleaning up the site.

Zac Trahan, program director of Texas Campaign for the Environment’s DFW office, views the announcement with “guarded optimism.”

“It’s good news but we really need to know more,” he said.

He urges Frisco residents to stay on top of cleanup efforts and ensure it’s done right.

“We can’t leave it to Exide. We can’t leave it to bureaucrats. We want a lot more public participation and citizen’s involvement.”

While Canavan said she is still concerned about lead buried on the Exide site, she chalked up a victory when she heard the plant was closing.

“If one child is helped by this, then my time and the group’s time is worth it.”

Although Mathew is relieved that the plant will no longer be operating, she is skeptical whether she can ever feel safe living around the site. She and her family plan to move.

However, she feels empowered by the outcome.

“When there’s a small group of voices, it still has an effect regardless of how small the group is,” she said. “Eventually, people will listen.”

Sign up for the weekly Green Source DFW Newsletter to stay up to date on everything green in North Texas, the latest news and events. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest.